Again, and Again, and Again

On obsessing over page 1

I’m bad at multitasking, especially writing. This spring and summer I needed to focus on promoting THE DOORMAN, and revising a screenplay, and I knew that my brain didn’t have room for more. So I hit pause on writing my next novel, accepting that I wouldn’t even open the file for months.

When I eventually returned to the manuscript midsummer, the first thing I did was write an entirely new Chapter 1, which had been percolating during the pause. This will not be the final time I reconsider the opening. I will edit that first scene an uncountable number of times, wrestling with every idea, every sentence, every word. For years.

Why? Am I filled with that much doubt? Am I that indecisive? Or am I just procrastinating moving forward?

No, and no, and no.

Skimming on the subway

Let’s say you’re trying to get your first book published. You’ve sent a carefully crafted query letter to literary agents, a one-pager that makes a case for why this book should exist in the world. Let’s say you’ve gotten a positive response—yes, please send us the full manuscript. You do, and you hold your breath.

Here’s what’s going to happen while you’re holding your breath:

The first person who’s going to read the manuscript is the agent’s assistant, who moved to NYC three years ago with an expensive English degree, got a part-time job at a bookstore and another part-time job SAT tutoring until she was able to land an internship in the legal department of an educational publishing company, until she was hired for a so-called entry-level job at a literary agency.

She lives in a dicey part of Brooklyn in a fourth-floor walk-up with two inconsiderate roommates and a few mice and an infinite number of cockroaches. To make even these modest ends meet, she needs to spend Saturday afternoons folding tee shirts at Old Navy, and an evening or two per month babysitting for her ex-boss’s brats.

She is never not broke.

Her official day job takes fifty hours per week, plus another twenty unofficially—reading books, reading manuscripts, reading reviews, watching films and television, listening to podcasts during her morning jog, evenings at bookstore events or drinks dates with other assistants, building her own network of peers in publishing, which like most businesses is premised on relationships, many of them forged outside the office.

This woman’s most precious commodity is her time.

She will leave her cubicle at 7:00 on a Tuesday, on her way to meet a vague acquaintance in Bushwick for a dive-bar beer, then dinner of five-dollar falafel from a food truck. There are no free seats on the subway. A creepy man is giving her the eye, so she sidles down the car. The train lurches to a stop between stations, and the PA system crackles something hard to decipher, maybe about a police action at Union Square. She’s going to be late. She sighs.

That’s the moment when she opens your manuscript. She’s sanding there in uncomfortable shoes with a heavy tote on her shoulder, a picture of Joan Didion smoking a cigarette. She reads page 1 carefully, page 2 faster, then skims to the end of the chapter. She has another half-dozen submissions loaded onto her tablet, and she intends to get through all of them before she returns to her desk tomorrow morning at 8:30.

The subway has still not moved when she mutters, “Nope,” closes your manuscript, and turns her attention to the next submission in her queue.

Quit early

If you stick around publishing long enough, eventually you won’t need to moonlight or babysit anymore. But you’ll trade in the babysitting for actual babies, you’ll add author dinners and PTA meetings and longer commutes to your weeknights, professional conferences and youth sports to your weekends. You may have more money, but you will never have nearly enough time for your pile. You will be sitting on cold aluminum bleachers, purportedly watching your kid run around some field, but in reality you will be reading submissions.

And you will have learned this: If you’re going to reject a manuscript, your life will be much better if you make that decision quickly. You’ll need to devote a tremendous amount of time and energy to pursuing the projects you love, so you shouldn’t spend unnecessary hours ruling things out. If you realize on page 5 that you’re never going to love something, don't read for a half-day to confirm it. Cut bait, move on.

Does this sound like injustice? I don’t think so. Because it’s not just this one reader on the subway who’s going to be grabbed, or not, on page 1. It’s also her boss. It’s also the assistant of every editor to whom the submission eventually gets sent, and their bosses. It’s also everyone who attends the editorial meeting or acquisitions meeting to weigh in. It’s also the editor-in-chief or publisher who needs to approve an offer. It’s also the marketing staff, publicity, the salespeople who will launch the book into the world. It’s also the bookstore buyers, the media reviewers, the entire publishing and bookselling ecosystems: Every one of these people has a Sisyphean pile.

And if everything breaks your way? Then it’s also potential readers in a bookshop, browsing. Does page 1 grab them? If not, they have a whole store filled with thousands of other options. If their answer standing in that shop is going to be no, then it’s this assistant’s job, standing on that subway, to say no, and save everyone else the losing effort.

This is a process of Darwinian natural selection, and page 1 is the evolutionary advantage.

This is not precisely what’s going to happen to me. I’ve been working with my agent for 15 years, so my next manuscript will skip the assistant-on-the-subway elimination round. But almost everything else will happen exactly the same way—all those other people are going to start reading my page 1, which is either going to grab them, or not, all the way to the bookstore browsers. And if those potential readers don’t like page 1, they’re going to put the damn thing down, even if they enjoyed my previous books. Those people don’t owe me another ten-plus hours of their lives, and thirty of their dollars, and they know it. I know it too. Just because I’ve been published before doesn’t mean I will be published again. Each book needs to justify itself.

Which is why I think it’s useful to accept this premise: If a book isn’t good on page 1, then ipso facto it’s not a good book.

What is a good book?

As with almost anything in publishing, this is a matter of opinion, of taste, and taste in reading is as varied as anything. There are many different ways for a book to be good, for many different types of readers. What sort of good are you aiming at? How do you want a reader to finish “I love this book because . . .”? This is one of the main goals of that one-pager—to figure out what you’re offering that the world might want, and how you’re delivering it.

This is not a comfortable exercise. “What’s good about my book?” isn’t dissimilar to asking, “What’s good about me?” which is a horrifying question to confront. It’s hard to see the answer clearly, it’s hard to drum up the nerve to form it into words. The hubris! It makes me want to throw up.

But if you can’t identify what it is that’s good about a book, maybe that’s because it isn’t. Which is something that’s far better to discover before you’ve spent a decade getting rejected.

And when you do figure out what’s good about your book? I suggest making sure that’s evident on page 1. Because if a book’s chief assets don’t become evident until page 10, chances are that no one is ever going to know it.

Back to the beginning

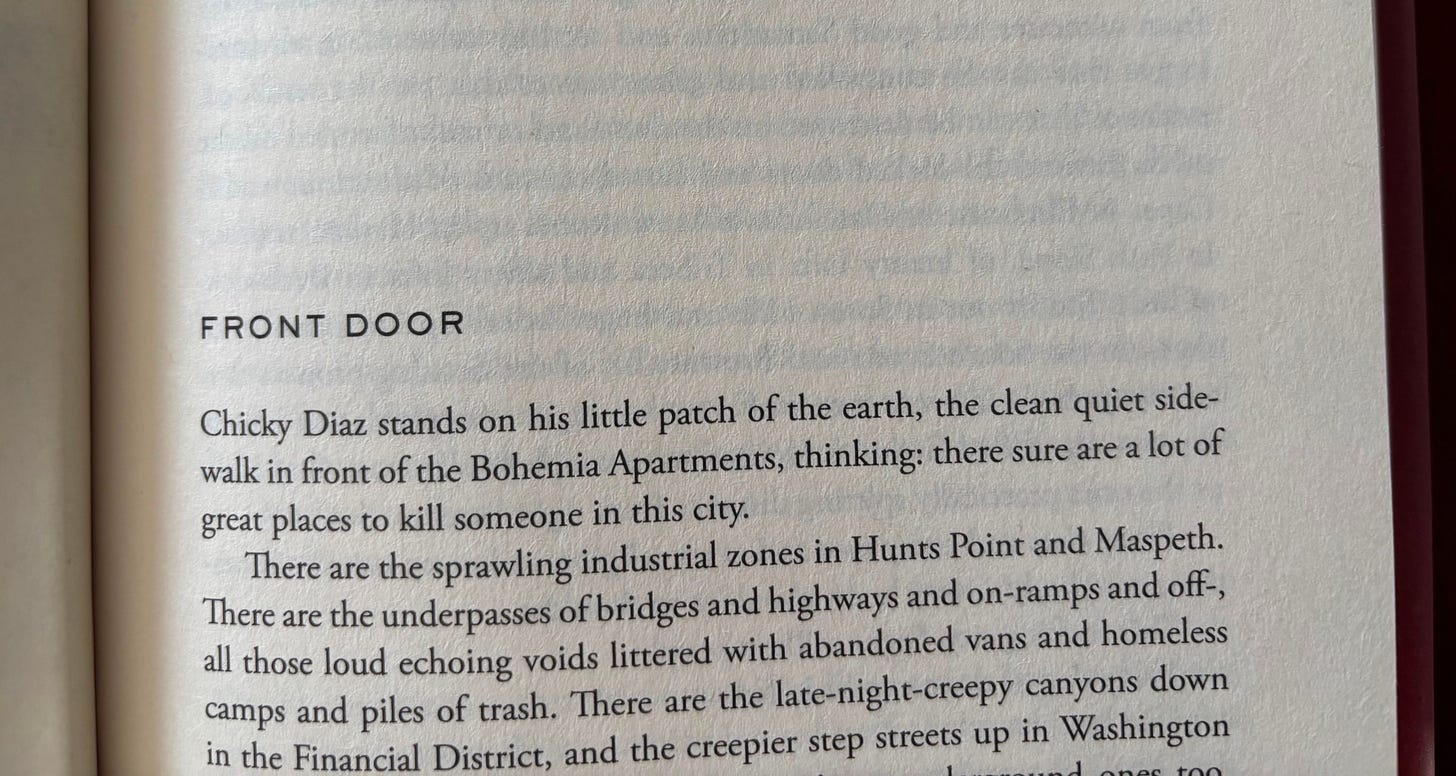

So I’m going to keep revisiting my opening again, and again, and again. Just because I had a first idea for how to start this book doesn’t mean it’s the best idea; it was just the first. I’ve published six novels now, and only one of them opens with the scene that I initially imagined. For the seventh, I’ve already come up with better ideas twice.

I know what I want to do on this new page 1, the type of good I want readers to think they’re going to get. I want to introduce the protagonist, the world she occupies, the predicament she finds herself in. I want to make it clear what genre this novel is, what type of plot, the stakes. I want to introduce conflict, peril, and suspense. I want the authorial voice to be clear—I want you know what you’re getting yourself into, with whom. I want you to feel compelled to turn to page 2. I want this beginning to make a new kind of sense after you’ve read the ending.

I want to do a lot in the short space of a couple hundred words, and I want to do all of it without making it obvious that I’m doing any of it.

That’s why.

I really enjoyed this article - thank you! I do have a question, though. Do you consider literary fiction to be part of this? I ask, because while I have read some stunning literary fiction, I have also started many literary fiction novels, only to stop thirty pages in and wonder if the author had ever been told they needed to hook their audience. ;-) Literary fiction doesn't always seem to require a plot, either. I get irritated because I have reworked my first chapters over and over to make sure they will hook the reader, but apparently not every genre is required to do this. What are your thoughts?

Thank you!!

Thoroughly enjoyed hearing you talk at the Pat Conroy Literary Festival. You shared a lot of really good information, thank you!