Making More Happen

On the second most useful note I've ever gotten.

When I was writing my first novel, I did what nearly everyone does, in basically the same way that everyone does it: I worked all by myself, writing, revising, doubting; then I asked a few trusted readers for feedback; then I rewrote, revised, doubted some more. Then I sent the manuscript to a fresh round of readers, and here’s where my story diverges from most people’s, because one of those readers was the legendary publisher of Alfred A. Knopf, Sonny Mehta.

Sonny and I had become friendly a decade earlier, when I was an editor, and we maintained a regular schedule of meeting for lunch or drinks, with cigarettes. It was extremely generous of Sonny to read that manuscript—before I had an agent, before the thing was a submission, when reading was mostly an act of friendship. As soon as I sent the ms. to him, he replied with an invitation to lunch a couple of weeks later. That was his deadline.

I held my breath.

We went to a middling Greek restaurant where I too used to conduct business lunches when I too worked at the company that was then called Random House, a block away. In typical publishing-lunch fashion, we talked about a lot of things while we ate lemon chicken, none of them what we were really there to talk about. Then the check arrived, Sonny put down his credit card, the waiter retreated.

“Chris,” he said, “I like the book very much.”

I exhaled.

“But,” he continued, “not enough happens.”

The waiter returned, Sonny scribbled his name, we rose, left. Out on the sidewalk, he lit a cigarette, and turned to me. “Good to see you.” He shook my hand. “Send me the next draft, will you?”

He walked back to his fancy job, and I walked toward a black hole of hopelessness.

Better vs. Less Bad

I look at editing as two distinct stages: the first is an ascent, trying to make the book bigger, better; the other is a descent, removing problems, trying to make the thing less bad. These missions aren’t unrelated, but they’re not exactly the same thing.

Manuscripts can include a huge number of problems, big and small and in between, that will detract from the reading experience: the middle is too slow, the dialogue is unnatural, the motivation isn’t credible, there are dangling modifiers everywhere plus a confusing subplot and, on page 378, a typo. Fixing problems is the goal of a lot of editing, especially in time-sensitive situations, which are nearly all situations. You don’t have forever, so you focus on the things that absolutely need doing.

In many manuscripts, but especially in fiction, the same simple solution presents itself again and again: delete something or other. Less, as I’m sure you’ve heard, is more. You’ve maybe even heard this from me.

But if you’re looking at a manuscript solely as an amalgamation of potential problems to repair—things to delete—you’ve already made a fundamental compromise: that the book is what it is, and the goal is making incremental improvements.

That’s not the only way to look at it.

Making More Happen

During the early edits, the focus is on the biggest problems, and with each successive stage the targets become smaller and smaller, as the job devolves from development editing to line editing, then handing the thing off to specialists for copyediting and proofreading, until eventually the work is just a matter of typos and end-of-line word breaks.

Is it the editor’s job to suggest solutions? That’s a matter of opinion. And that’s also dependent on the editor’s temperament, and workload, and commitment. Also on what the author seems to want, or need. There’s no universal answer.

When I was writing those early drafts of The Expats, I didn’t yet know what I wanted, or needed, or expected. I’d spent an afternoon at my dining table with Jamaica Kincaid, turning nearly every page, looking at PoV issues; from other readers, I’d gotten long letters of point-by-point critique. It was clear to me what I was supposed to do with their specificities.

I was less clear about Sonny’s couplet. I like the book very much. But not enough happens. I didn’t even know if the first part was true; maybe he was just being polite. It was up to me to decide what to do with this feedback.

The choice I made was along the lines of Pascal’s Wager, to believe whatever would give me the greatest odds of eternal rewards: that he really did like the book, but that not enough happens.

So: what more can happen?

I confronted that challenge. I re-read, for the bazillionth time, the manuscript. But this time I wasn’t looking for old problems to remove; I was looking for new features I could add. This character: can she do something else? This relationship: can it be more complex? This plot line: can it have an additional twist? This ending: is this really the end? Or can there be another ending after the ending? Can there be a big paradigm shift somewhere, a reveal that turns the entire story on its head, and puts everything in a new light?

This was what I spent the next few months doing: making the characters bigger, the conflicts bigger, the tension bigger, the story bigger. Making more happen.

Then I got back in there to remove problems new and old, to make the thing 10 percent shorter, to clean it up, to send it out to an agent, to clean it some more, to submit it to publishers—

“He’s on a Plane”

It was midwinter break. I’d taken my kids to the Union Square theater for a movie that had barely begun when my agent called. The manuscript had been submitted to publishers a few days earlier, and now one of them wanted to make a preemptive offer—to take the book off the table, end the shopping process today. The offer would be good for the next few hours, till the end of the business day. Would we entertain this?

This may sound like a no-brainer, but it’s not. My agent and I discussed the pluses and minuses. For me, one of the big minuses was that this publisher was not Sonny. “Can we find out what he thinks?” I asked. It took a minute to learn that he was en route home from India, and wouldn’t be reachable until it was too late.

We debated it every which way. Then we accepted.

When my kids were babies, I’d given up cigarettes, for the obvious reasons, plus it was becoming increasingly illegal and inconvenient and expensive to smoke in New York City. Sonny did not quit. So our drinks dates evolved into me bringing a bottle of red wine to his apartment, where he was free to smoke while drinking, one of life’s great combinations.

We often discussed what makes a book special—the Nobel Prize winners that Knopf seemed to specialize in, or Stieg Larsson, or Fifty Shades of Grey. There are many different ways to be special. And this is one that I decided to aim at, for every book. When I’m editing a first draft, I don’t focus on removing problems, but instead I ask myself this question:

What more can happen?

This question is relevant in an obvious way to the type of books I write: suspense fiction, with complex plots. But I think it’s perhaps even more true for fiction that doesn’t feature a lot of action, doesn’t have much plot. Even if the things have nothing to do with violence or crime or espionage or huge sums of stolen money, things still need to happen. That’s what makes it a story.

I don’t think there’s ever just one reason that a book achieves success. Sometimes one of those reasons is that the book is special, but that in itself isn’t enough, and that’s not even a requirement. The Expats was successful because my agents did an excellent job of generating enthusiasm, and because Crown did an excellent job of publishing the thing—advertising, marketing, reviews, media, blurbs, cover, everything—and because the moment was right, and because we were lucky. And I think the published version was special.

And I know this: the version I shared with Sonny was not. At the time, I was confident that it was a salable, publishable manuscript; I still believe this. That ms. could’ve found an agent, and a publisher, we would’ve fixed some problems, the book would’ve been published. But it would not have been nearly as special. Because so much of what people loved about the book were things that I added after Sonny’s piece of seemingly unactionable vagueness, which turned out to be second most useful note I’ve ever gotten.

The most useful? It’s inseparable from one of my fall events. I’ll talk about it then.

“Not enough happens” is an accusation that might also be leveled at almost anything—a ballgame, a book publication, a life.

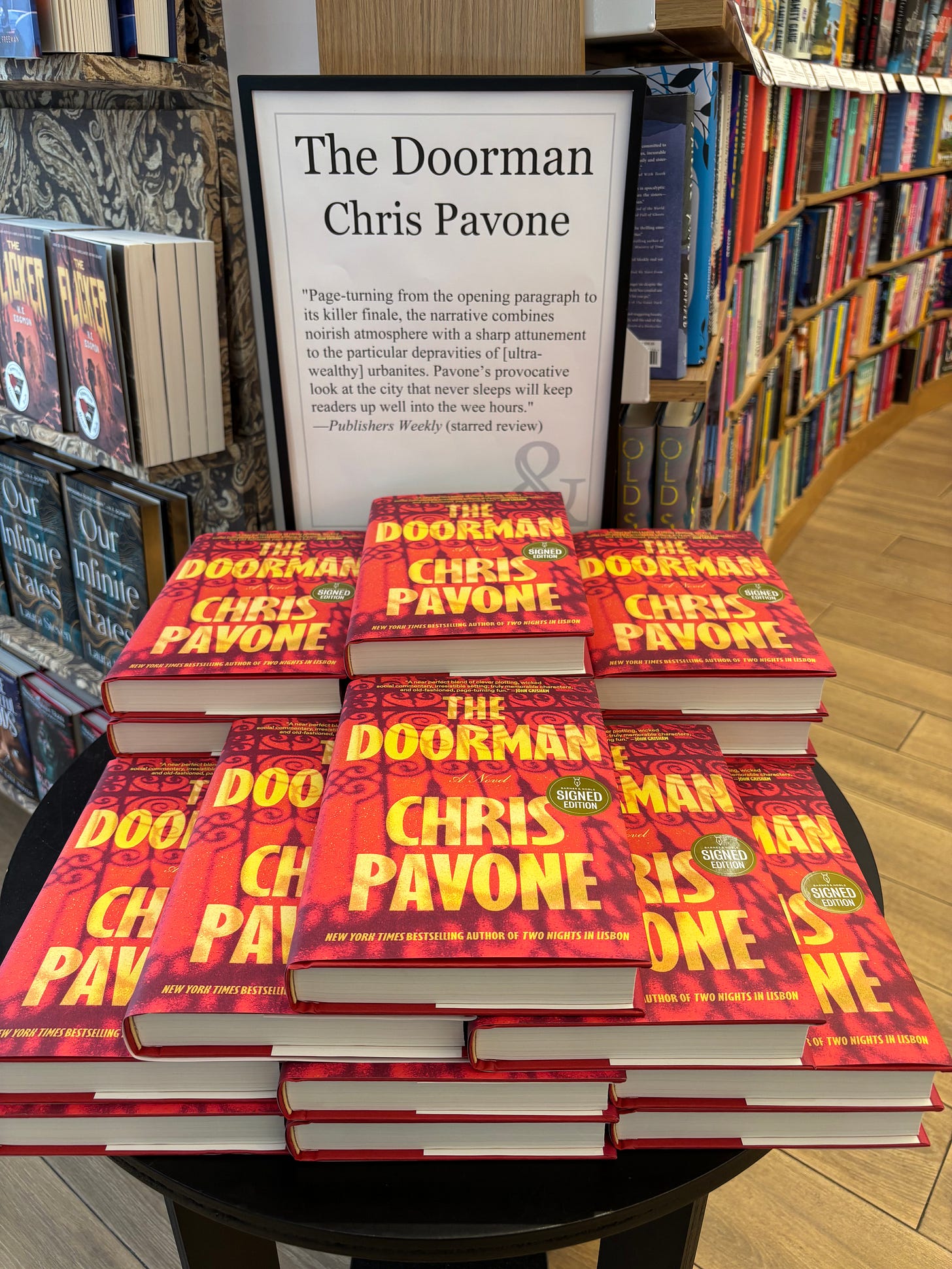

Although The Doorman went on sale 10 Tuesdays ago, the first time I stood in front of people to talk about the book was 10 months ago, when a bunch of independent booksellers visited my publisher’s offices to hear about the forthcoming lists. Publication is a long process, for every book. And there comes a moment when everyone wants to take their foot off the gas, change lanes, move on. For The Doorman, that moment could be now.

But it’s not. I’m still asking: What more can happen?

Last week I made the rounds to sign inventory at my local shops, where the book was prominently displayed in windows, and face-out on shelves, and on display tables; it even has its own little table at the Upper West Side Barnes & Noble. And I still have nearly as many events on the road ahead as I do in the rearview—some private book clubs, some podcast recordings, and these public events (including all the airports-at-dawn days for this book):

9 August: East Hampton Library Authors Night

26–28 September: Aspen CO Literary Festival

10 August: The Back Room virtual event

13 September: Cutchogue NY Free Library

11 October: Morriston NJ Book Festival

25 October: Pat Conroy Literary Festival, Beaufort SC

29 October–2 November: Toronto International Festival of Authors

8–10 November: Sharjah International Book Fair

11 November: Charleston SC Literary Festival

This is Wally, wanting more to happen.

Wow. This was so thought provoking. Thank you. (And it made me want to pick up your book!)

Excellent post. Thanks, Chris!