Book Music

On writing advice from Pat Conroy

I recently discussed the second most valuable piece of writing advice I ever received. And the most important? I got that 30 years ago, back when I was a young copy editor at Doubleday.

It’s not just writing that’s hard to break into. The publishing business itself is a tough door to get through, which I did via three different entry-level jobs: marketing temp for a professional-journal publisher; jack-of-all-trades for a free weekly paper; editorial assistant for puzzle magazines. During the couple of years that I held these odd jobs, I took continuing-ed night classes in book production, copyediting, and proofreading. These skills led to freelance work, which led to my first real job in books, as a junior copy editor at Doubleday.

The essence of this job was to try to get every book to press with as few errors as possible, on schedule. In those days Doubleday published a great breadth of books—literary and commercial fiction, serious nonfiction, unserious nonfiction, illustrated books, cookbooks, business books, reference works, we even had a whole religion department. Almost every book crossed my desk. Some of these books were interesting to me, others less so; some were hugely profitable, and some I thought were great, and some were even both.

Doubleday was a successful company, the bottom line was good, so was the mood, Jackie Onassis (!) worked there, and my cohort of young colleagues were smart ambitious people who’d come to New York City to work in books; I had a great time with those people. I spent my weekdays nitpicking grammar with a waxy Col-erase carmine-red pencil, and my weekends doing freelance work to bridge the gap between my salary and the barest minimum of what it actually cost to live in New York City.

I loved this job, and I made a habit of volunteering to do more of it. Who’s going to spend the weekend on a rush proofread? Me. We need a guinea pig to test a computer program? Yes, I’ll do it. Can you pull an all-nighter to slug the 2nd pass against the 1st of the New Catechism of the Catholic Church—in Spanish? Um, yes. Not because I expected something in return, but for the satisfaction of doing more, of learning more. These special assignments were their own reward.

The Free-Agent Superstar

Commercial publishing is a bestseller-driven business, but it’s rare for huge bestsellers to emerge fully formed from the muck of the submissions pile. Debut novels tend to sell poorly, 2nd novels worse, then hopefully the numbers bounce back for Book 3, the audience grows, and in the dream scenario Book 4 or beyond hits some zeitgeist, and boom—The Da Vinci Code, or The Underground Railroad. (Both of these were Doubleday books, long after I left the joint.) A single mega-bestseller can generate as much profit as the other 100 books that a publisher releases in a given year, combined. Big books are what keep the lights on.

In publishing, as in Major League Baseball, there are two routes to getting a superstar onto your team. The low-odds, low-cost approach is to draft a promising young player as a teenager, develop him through years and years in the Minor Leagues, and hope; the vast majority of these prospects don’t pan out. The high-odds, high-cost route is to buy an established superstar in free agency.

Thirty years ago, Pat Conroy was one of the most famous writers in America, and he’d come to Doubleday as a free agent, following his editor Nan Talese from Houghton Mifflin. Beach Music was to be his first season on the new team. The book was hugely important to the company’s bottom line, and the substantive revisions were taking a long time—too long. Doubleday really wanted to get that book out into bookstores, and get its revenue flowing in.

The publisher made the extraordinary decision to move Pat from his home in San Francisco to a hotel on the Upper East Side of Manhattan so he could finish the work. Someone needed to do the unusual job of checking in on this semi-kidnapped author every day—that he was making progress, and not spending his days cooking pasta. The natural person for this job was that junior copy editor who volunteered for every extra-credit assignment.

And so it came to pass that for a few weeks in the spring of 1995, I began most days by walking from my basement studio apartment on the west side, across Central Park, over to Pat’s far nicer home on the east side, where at 9:01 a.m. I’d knock on his door. Pat would hand me a messy sheaf of marked-up typescript plus new inserts that he’d handwritten on yellow pads—yesterday’s work.

One of my tasks was to ensure that these revisions fit with the rest of the book—grammar, style, continuity. Another was simply to be a daily presence badgering this poor man. Those two tasks turned out to be far easier than the unexpected challenge of deciphering Pat’s handwriting; chicken scratch is a generous way of describing some of the more rushed passages, and it was not unusual for there to be food stains. I could spend ten minutes just trying to figure out a single word, and still fail, and have to annoy Pat. “What’s this word? Sorry. And this one?”

We took long walks. Pat knew I wanted to be a writer—I’d told him—and he knew I wanted advice, but every time the conversation headed that way he deflected, turned the subject back to me, peppering me with questions about my job, my family, my dating life, whatever. It was frustrating.

Then we came to the end. This happens with every book, for copy editor and editor and author alike, working for weeks or months or years on a thing, and then one day it’s over, forever. We had a final meeting with Nan at her house, then Pat and I walked homeward, having one of those awkward conversations you have at the end of something. That was when he finally gave me what I wanted.

The Festival

I’m writing this on an airplane, headed home from the 10th annual Pat Conroy Literary Festival in Beaufort SC. As with most festivals, this one felt much more like a weekend-long party than anything that might be called work. To me it’s not work to talk about writing on stage, nor to meet readers, nor to share long meals with other novelists, nor to sit in the audience and listen to other people talk about their books. The hardest part is that it’s tiring. But the same can be said of every type of fun.

The festival’s opening-night reception was held at a grand old waterfront house that’s referred to as the Big Chill House because it’s where the movie was filmed. But our party was there because it’s also the Great Santini House, a location for that film too, and co-star Michael O’Keefe was one of the festival presenters; he received an Academy Award nomination for his portrayal of Ben Meechum (aka a young Pat Conroy). Michael has had an illustrious career in the four and a half decades since (during which he also managed to get an MFA in poetry!), but he credits that first big role with launching him. Much to my surprise—very nearly a spit take—Michael used part of his remarks to urge everyone to read The Doorman.

I’m immensely grateful for that suggestion, and indeed for everything and everyone over the tremendously fun weekend, but even more grateful for why I was invited: because of that month in 1995 that I spent with Pat. It then took me more than a decade and a half before I published my first novel, but his advice was with me all that time. It’s still with me today.

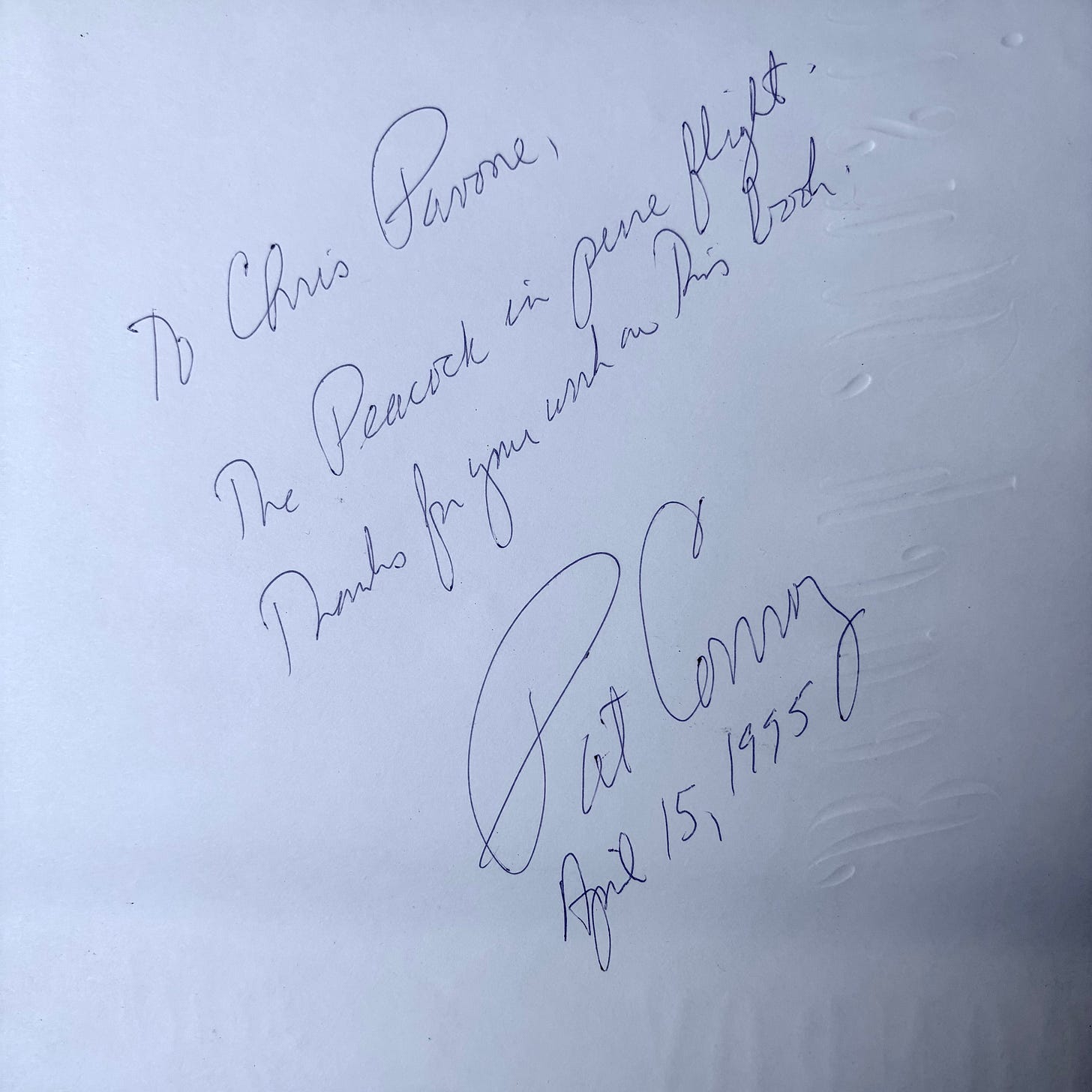

Note that the barcode is missing from that blank box on this book jacket, because it’s not a real jacket: it’s the printer’s proof that I brought to the author for his OK before going to press. Once his approval signature on the back of this proof was noted (with extra commentary for me), this document became what’s known as “foul matter”—something that’s no longer the most recent pass, no longer live, no longer needed. Later, once a book is printed and distributed, all the foul matter—manuscript versions, typeset pages, cover proofs, style sheets, etc.—collectively becomes “dead matter.” These were my favorite phrases in the business.

The Advice

“Pavone,” he said, walking through Central Park. Pat is the only English speaker I’ve ever met who knew what my name meant, and he relished saying it, pronouncing the Italian word with a flourish. He never, ever used my first name.

“I know you want advice from me, and I’m going to give it to you.” We were walking through the zoo in a cold spring drizzle. “Listen,” he said, “to other people’s stories.” He stopped and turned to me, those twinkling blue eyes. “Listen carefully.”

Does this seems obvious? Maybe. But it was that emphasis that struck me as the point, a distillation of something crucial, not just as a writer, but as a person. Carefully.

And in that moment I realized that all those conversations about my life, that wasn’t Pat deflecting. That was Pat working.

And I then understood this: Being a novelist isn’t something you do just when you’re writing. It’s something you do all the time.

Hi, Chris,

Thanks for your recent commentary. Like you, I worked long weeks as a Crown/Random House rep. I loved my time at Crown and would do lots of extra work because I wanted to (not so much with Random, more like corporate America). Lots of 50-60 hour (Mon-Sat) work weeks. Weeks at a time on the road. Crown was Family, With Random we were cyphers. Alan Mirken was a friend and mentor, not just a boss.

Jim

What an amazing story!